About Songs of Political Persuasion

Presidential Noise

Presidential campaigns are noisy affairs. We hear the thunderous roar of clapping, cheering crowds, the flashes of a thousand cameras, and slogans ringing in the air. Whether it be the brass bands, drums, fifes, and fiddles of yore, the sounds of Bruce Springsteen and U2 over the loudspeaker, or the strains of a crowd erupting in their own rousing cadence, music is there as well.

Watch any of the presidential candidates take the stage at their 2024 rallies and you will hear a pop song ringing out in the background. Nikki Haley, like several Republican candidates before her, uses Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger;” Ron DeSantis, with a nod to the WWE, offers Rick Derringer’s “I Am a Real American;” Chris Christie salutes one of his favorite artists, Bruce Springsteen with “No Surrender”; Asa Hutchinson goes country with Chris Stapleton’s “Arkansas;” Tim Scott kicks it old school style with The Gap Band’s “Burn Rubber On Me (Why You Wanna Hurt Me),” and, as he did in 2016 and 2020, Donald Trump walks on to Lee Greenwood’s perennial favorite “God Bless the U.S.A.”

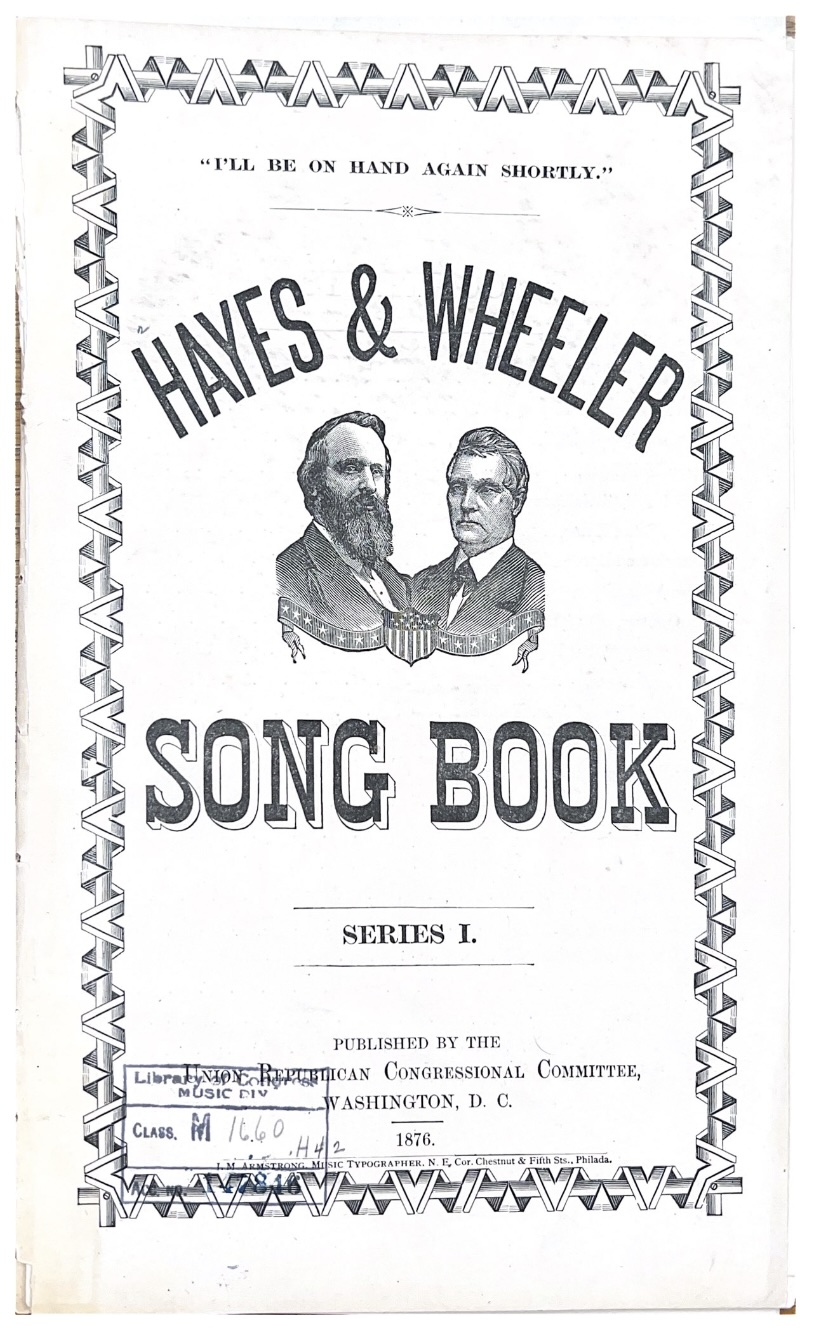

We all may recognize the pop songs that the candidates typically use in their campaigns today, but what did campaign music sound like in the 19th century? Before the emergence of radio and television, political parties distributed campaign songs in “songsters,” small booklets that typically provided lyrics and indicated the appropriate melody to go with them. Some songsters included three- or four-part a cappella choruses at the songs’ refrains. The candidate’s supporters (and sometimes glee clubs) performed these satirical or didactic songs at political meetings, parades, and rallies. Although songsters were widely circulated and the songs were popular during a given campaign, the music faded into obscurity shortly after.

While a handful of scholars have turned a critical lens to song lyrics and the politics therein, these songs have indeed passed into history as only a small number have been recorded.[i] Thousands of songsters lie on the shelves of archives, their ephemeral, yet politically and culturally significant content mostly forgotten outside of academic circles. Over the past year, the Trax on the Trail VIP research team and the Max Noah Singers have brought together archival research methods, music analyses and arranging, and music technology to engage with this important question.

Beginnings

Enter: Songs of Political Persuasion, a website and research project devoted to the study and performance of campaign songs published in songsters.

We began by selecting a specific period of focus. We settled on 1840 to 1918 for several reasons. 1840 was the first campaign with popular participation, and it was the first where singing was promoted as a worthy accompaniment to other campaign-related activities. Consider this report from the People’s Convention of Ohio in 1840:

The cabin was surrounded by a dense mass of people, and the calls were loud for a repetition of the song – again and again was it repeated, until many caught the words of the verses and sung them over for the benefit of others would could not get within hearing distance. This musical propensity spread rapidly among the crowd. Songs were written, printed and in the hands of hundreds in a short time. Everybody was singing.[ii]

We selected 1918 as the end date, as just a few years later, radio emerged as an important platform for political communication and group singing in connection with campaigns became less relevant. Moreover, we wanted to focus on campaign songs that had never been recorded, so music pre-1900 afforded a broader palette of choices. While 19th-century campaign music was disseminated via various media, including newspapers, broadsides, and sheet music, for our project we decided to focus on songsters.

With these parameters in place, we consulted William Miles’ Songs, Odes, Glees, and Ballads: A Bibliography of American Presidential Campaign Songsters, which catalogs presidential campaign songsters. While public libraries and universities across the US house songsters, the largest collection is located at the Library of Congress. After we created a list of 120+ songsters that met our parameters, we narrowed the list to fifty-eight, which included broad representation of parties and candidates. Since we had a skilled choir at our disposal, we only considered songsters with three- or four-part arrangements of either SATB, SAB, or TTBB music. This narrowed our list down further to thirty-six.

We did not have the time or resources to record all the songs that we compiled. Therefore, we decided to conduct a comprehensive review of all songsters in our collection, and then select the songs that would most effectively further our goal of teaching the public about the historical use of music in presidential campaigns. The team’s process was governed by the following guidelines:

- Lyrics that are spicy, comical, or historically significant

- Catchy tune

- Representation from all parties

- Inclusion of successful and unsuccessful candidates

- Variety of moods (comical, serious, etc.)

- Diversity with regards to musical style

- Broad coverage of the period under consideration

- Representation of women composers

- Inclusion of professional and amateur composers

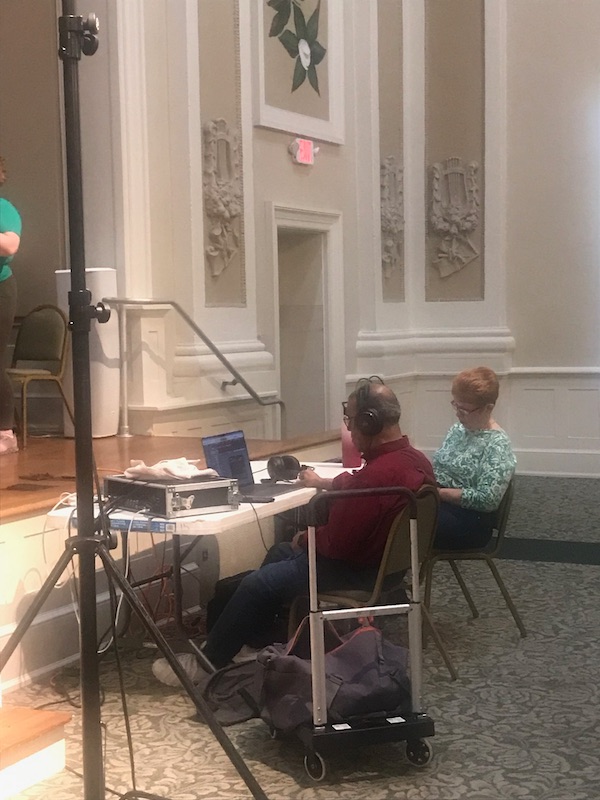

The team split up the songsters and individually worked to identify the songs that best met our criteria. Next, we gathered in meetings to sing through the music and conduct preliminary analyses of the songs. The last step was to have a rehearsal choir sing through the final list of eighteen selections. This brought the final count to twelve songs. Using an open access music notation platform, team member Riley Greer created modern editions of the songs. Dr. Jennifer Flory reviewed and edited her work. In April of 2023, we worked with Karl Wicker at Arie Cantate to record the songs that are now available through our website.

Why songsters?

Campaign songsters are an important part of US history that allows us to gain insight into how candidates and their supporters harnessed music to persuade voters. In recent years, music heard on the campaign trail has received a lot of attention in the mainstream press; however, there is little public knowledge regarding the roots of this tradition in the mid-19th century. The academic work on this topic indeed speaks to scholars with an interest in the history of electioneering, but we believe our historically informed recording will stimulate broader interest in the topic and serve as a didactic tool that will allow educators, students, and the public to engage in this topic with a more critical ear.

Songs of Political Persuasion is a small part of a larger project at Georgia College called Trax on the Trail, a website and research project devoted to the study of music and sound in contemporary US presidential campaigns. It is our mission to promote a more critical evaluation of how music and sound shape the public’s perceptions of presidential candidates. You can learn more about the Songs of Political Persuasion Project and music on the 2024 campaign trail at www.traxonthetrail.com.

[i] Irwin Silber, Songs America Voted By: With the Words and Music That Won and Lost Elections and Influenced the Democratic Process (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1971), 18.

[ii] Report from the People’s Convention of Ohio, February 22, 1840.